Donegal, 2012

Fifty years ago, I asked my Aunt Miriam in England what she knew of her father’s father, who was born in Ireland, and she said, “He rowed on Lough Swilly.” She also told me of two recent family drownings on that body of water, the deepest lake in Europe and one open to the sea.

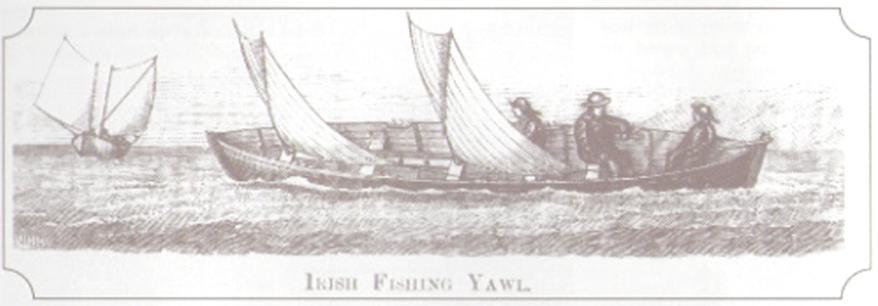

About twelve days ago, in June 2012, I stood with the genealogist Seoirse O’Dochartaigh on the site at Farland Point in Co. Donegal, where he had discovered, through extensive research, that my great- grandfather Charles and his brother James, known as “the boat-builder,” shared a small house during the time they made a living rowing people over to nearby Inch Island. They later moved onto Inch Island, and it is from there that Charles and his wife Sarah and their son James, my grandfather, emigrated to England. The Browns who remained in Donegal have lived in that area since at least 1611, when King James I granted a charter to a John Brown to run a ferry service on Lough Swilly.

It has been my passion these last years to get to know that ancestral country, to take long walks in all weathers, to make the acquaintance of living relatives—cousins (Cecil Brown, Alan and Kenneth Brown, Audrey Brown Hamilton), members of the “boat people” of Inch Island, as they are known–and also to pursue the connection between the building of boats and the word-building I do when I write words for music—libretti, lyrics—something I have been doing, along with poetry, for almost fifty years.

My essay “Words for Music” in What the Poem Wants (Carnegie Mellon University Press, 2008) begins this way:

Writing words for music is like building a boat rather than a house—you want something firm, buoyant, that will float when the music arrives. Build too heavy, and things sink. (And most words for music on the page are as about as interesting as boats on sand.)

When I made my first visit to Co. Donegal in 2006 and discovered the “boat people,” and various evocative sites near the magnificent Lough Swilly (“Lake of the Shadows”) , including Farland Point, the two cemeteries where family members are buried, and the area (Castle Hill) in which my grandfather was born, I knew I had come to a place I would always want to return to. At the same time, I knew I could never uncover many of its secrets, and I am necessarily “living the questions” of my heritage and ancestral country, to use Rainer Maria Rilke’s phrase, rather than anticipating answers from the long-vanished dead.

Another very fortunate thing that happened on this most recent visit t, which included some good further conversation with my cousins, and with Seoirse, was my meeting again with Donal MacPolin, an author I had talked with in 2006 at the Inishowen Maritime Museum in Greencastle, where the Violet, the ferry boat rowed on Lough Swilly by family members for several decades, was on central display. At that time, Donal had signed my copy of his book The Drontheim: Forgotten Sailing Boat of the North Irish Coast with these words: “You’re a long way from Minnesota.”

On this occasion, he not only signed a copy of his new book, The Donegal Currachs, but gave a talk as part of the Donegal-wide Celebrate Water festival on “Boatbuilding Therapy” in which he spoke of building currachs by hand, first on his own, then with a number of different groups, including breast cancer patients at the hospital in Letterkenny, with at-risk teenagers, and the like. (I was reminded of Minnesota’s own innovative Urban Boat-Building Project, which has at-risk youth involved in similar work.) I know from my own experience, as a writer and teacher, the value of the specificity of such tasks, the way they provide focus and centering when the mind is being pulled in too many directions at once.

What was especially thrilling for me, and relevant to the association I am making between writing for music and the building of boats, was Donal’s description of his process: this involves the weaving into a light frame of two kinds of woods, willow and hazel (twigs, rods), and taking into account, as the work goes on, the need of those woods, even after they are covered with tarred canvas, to stretch and bend, to continue to be alive and maintain their flexible personality.

Such is the way with my writing for music also—there must be both resistance, as Igor Stravinsky says of the writing of actual music, and also a certain springiness in the materials. I find these connections deeply stimulating to the imagination, feeling sustained in my artistic life both by the ancestral belonging and the similarities of process I continue to uncover.

The same remains true for the physical body as I have entered my 73rd year and continue basic yogic stretching–that I must “befriend the bending” in order to do stay reasonably limber in both body and spirit. Similarly, I need to be flexible and nimble in my collaborating with composers such as Stephen Paulus and Craig Hella Johnson, adapting and adjusting, even radically, my initial words and phrasings to the sometimes unexpected musical demands of rhythm, pitch, and the like.

This latest visit to Ireland, my fourth in six years, has yielded a harvest of notes, information, and speculation; I plan to intensify my exploration of these intriguing connections and lay out the acquired learning, speculation and new thought in an extended essay, which will be taking shape over the next months.

In a program note, “The Boat People,” which I wrote for the Minnesota Orchestra program in connection with a 2008 performance of To Be Certain of the Dawn, a post-Holocaust oratorio I wrote with Stephen Paulus in 2005, I concluded with the following:

“It is a collaboration I treasure. I’m not a musician, after all; I’m just descended from boat people from the southern shores of Lough Swilly,

and I’ve been working at my trade along the years, shaping and fitting the various woods of words, never able (or inclined) to anticipate what watery acres these craft, of all sizes, may be lucky enough to be launched upon. To Be Certain of the Dawn is the largest sea, the deepest, on which I have been privileged to see them floating.”

I am honored, I should add, to be descended from those who not only built boats but for so long were committed to bringing people from one place to another over water (yet one more connection which the writer in me finds uncanny). It has been written of the family that they “never left anyone stranded. All one had to do was wave a white handkerchief or a lighted newspaper on Fahan jetty to signal a request to be ferried across to Rathmullan.” Now that’s a belonging I am proud of.